-

International Letter Writing Week. Paintings

Japan 1996.10.07

In issue: Stamp(s): 6

Printing: on fluorescent paper, as pairs (1+2, 3+4, 5+6 stamps)

-

Number by catalogue: Michel: 2419 Yvert: 2297 Scott: 2541

Perforation type: 13 ½x13 ½

Subject:

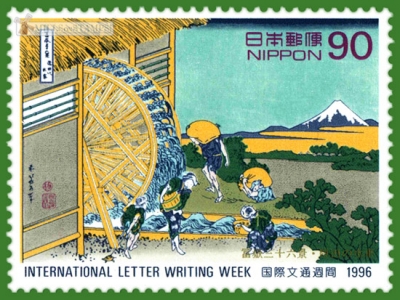

90 yen. Ukiyo-e* "Watermill and mount Fuji", by Hiroshige**

Additional:

*Ukiyo- e (浮世絵 ?), "pictures of the floating world", is a genre of Japanese woodblock prints (or woodcuts) and paintings produced between the 17th and the 20th centuries, featuring motifs of landscapes, tales from history, the theatre and pleasure quarters. It is the main artistic genre of woodblock printing in Japan.

The "floating world" (ukiyo) refers to the impetuous urban culture that bloomed and was a world unto itself. Although the traditional classes of Japanese society were bound by numerous strictures and prohibitions, the rising merchant class was relatively unregulated, therefore "floating."

The art form rose to great popularity in the metropolitan culture of Edo (Tokyo) during the second half of the 17th century, originating with the single-color works of Hishikawa Moronobu in the 1670s. At first, only India ink was used, then some prints were manually colored with a brush, but in the 18th century Suzuki Harunobu developed the technique of polychrome printing to produce nishiki-e. Ukiyo-e were affordable because they could be mass-produced. They were mainly meant for townsmen, who were generally not wealthy enough to afford an original painting. The original subject of ukiyo-e was city life, in particular activities and scenes from the entertainment district. Beautiful courtesans, bulky sumo wrestlers and popular actors would be portrayed while engaged in appealing activities. Later on landscapes also became popular. Political subjects, and individuals above the lowest strata of society (courtesans, wrestlers and actors) were not sanctioned in these prints and very rarely appeared. Sex was not a sanctioned subject either, but continually appeared in ukiyo-e prints. Artists and publishers were sometimes punished for creating these sexually explicit shunga.Ukiyo-e prints were made using the following procedure:

1. The artist produced a master drawing in ink

2. An assistant, called a hikkō, would then create a tracing (hanshita) of the master

3. Craftsmen glued the hanshita face-down to a block of wood and cut away the areas where the paper was white. This left the drawing, in reverse, as a relief print on the block, but destroyed the hanshita.

4. This block was inked and printed, making near-exact copies of the original drawing.

5. A first test copy, called a kyōgo-zuri, would be given to the artist for a final check.

6. The prints were in turn glued, face-down, to blocks and those areas of the design which were to be printed in a particular color were left in relief. Each of these blocks printed at least one color in the final design.

7. The resulting set of woodblocks were inked in different colors and sequentially impressed onto paper. The final print bore the impressions of each of the blocks, some printed more than once to obtain just the right depth of color.**Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川広重 ?, 1797 – October 12, 1858) was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, and one of the last great artists in that tradition. He was also referred to as Andō Hiroshige (安藤広重) (an irregular combination of family name and art name) and by the art name of Ichiyūsai Hiroshige (一幽斎廣重).

Hiroshige was born in 1797 and named "Andō Tokutarō" (安藤徳太郎) in the Yayosu barracks, just east of Edo Castle in the Yaesu area of Edo (present-day Tokyo). His father was Andō Gen'emon, a hereditary retainer (of the dōshin rank) of the shōgun. An official within the fire-fighting organization whose duty was to protect Edo Castle from fire, Gen'emon and his family, along with 30 other samurai, lived in one of the 10 barracks; although their salary of 60 koku marked them as a minor family, it was a stable position, and a very easy one — Professor Seiichiro Takahashi characterizes a fireman's duties as largely consisting of revelry. The 30 samurai officials of a barracks, including Gen'emon, oversaw the efforts of the 300 lower-class workers who also lived within the barracks. A few scraps of evidence indicate he was tutored by another fireman who taught him in the Chinese-influenced Kanō school of painting.

Legend has it that Hiroshige determined to become a ukiyo-e artist when he saw the prints of his near-contemporary, Hokusai. (Hokusai published some of his greatest prints, such as Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, in 1832—the year Hiroshige devoted himself full-time to his art.) From then to Hokusai's death in 1849, their landscape works competed for the same customers. More likely though, like many other low-ranked samurai, Hiroshige's salary was insufficient for his needs, and this motivated him to look into artisanal crafts to supplement his income. It was easy to balance his job and his artistic pursuits, as a fireman was only intermittently busy.

His natural inclination toward drawing marked him for an artistic life: as a child, he had played with miniature landscapes, and had already produced an impressive painting in 1806 of a procession of delegates to the Shogun from the Ryukyu Islands, which was remarkably accomplished given his young age. He began by being taught the Kano school's style by his friend, Okajima Rinsai. These studies (such as a study of perspective in the Dutch images imported) prepared him for an apprenticeship. He first attempted to enter the studio of the extremely successful Utagawa Toyokuni but was rejected. Thus, he eventually embarked on an apprenticeship with the noted Utagawa Toyohiro instead of with Toyokuni. He was rejected again on his first attempt to enter Toyohiro's studio, but later accepted at the age of 15 in 1811. Toyohiro bestowed upon him the name "Utagawa" after only a year (instead of the usual period of two or three years). Hiroshige later took his master's name, becoming "Ichiyūsai Hiroshige."

In his early apprenticeship to Toyohiro, he showed little sign of artistic genius and did not publish many works. Despite earning an artistic name ("Ichiyūsai Hiroshige") and school license at the young age of 15, Hiroshige's first genuinely original publications came six years later in 1818. His Eight Views of Lake Biwa and Ten Famous Places in the Eastern Capital were moderately successful.This was also the year in which he was commended for his heroism in fighting a fire at Ogawa-nichi. However, it was not until the publication of Hiroshige's Famous Places in the Eastern Capital (1831) that he attracted real public attention. It is speculated that he whiled away the interim between his initial apprenticeship and 1818 engaging in work for Toyohiro's school, such as painting fans and other small items. This sort of work supported him as he continued to study the Kanō and Shijō painting styles. These were merely precursors to the series of prints that made him famous. In 1832, Hiroshige was invited to join an embassy of Shogunal officials to the Imperial court. As his son, Nakajiro, could handle his fireman duties, Hiroshige joined the delegation. He carefully observed the Tōkaidō Road (or "Eastern Sea Route"), which wended its way along the shoreline, through a snowy mountain range, past Lake Biwa, and finally to Kyōto. His series of prints, The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, was extremely successful, and Hiroshige's reputation was assured.

In 1839, Hiroshige's first wife, a woman from the Okabe family, died. Hiroshige re-married to O-yasu, daughter of a farmer named Kaemon.

Hiroshige lived in the barracks until the age of 43. Gen'emon and his wife died in 1809, when Hiroshige was 12 years old, just a few months after his father had passed the position on to him. Although his duties as a fire-fighter were light, he never shirked these responsibilities, even after he entered training in Utagawa Toyohiro's studio. He eventually turned his firefighter position over to his brother, Tetsuzo, in 1823, who in turn passed on the duty to Hiroshige's son in 1832.

In his declining years, Hiroshige still produced thousands of prints to meet the demand for his works, but few were as good as those of his early and middle periods. He never lived in financial comfort, even in old age. In no small part, his prolificacy stemmed from the fact that he was poorly paid per series, although he was still capable of remarkable art when the conditions were right — his great One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景 Meisho Edo Hyakkei ) was paid for up-front by a wealthy Buddhist priest in love with the daughter of the publisher, Uoya Eikichi (a former fishmonger).

In 1856, Hiroshige "retired from the world," becoming a Buddhist monk; this was the year he began his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. He died aged 62 during the great Edo cholera epidemic of 1858 (whether the epidemic killed him is unknown) and was buried in a Zen Buddhist temple in Asakusa. Just before his death, he left a poem:

"I leave my brush in the East

And set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places in the Western Land."

(The Western Land in this context refers to the strip of land by the Tōkaidō between Kyoto and Edo, but it does double duty as a reference to the Paradise of the Amida Buddha).